For the last two years the SSAW Collective have run a campaign in the run up to Valentine’s - ‘Why buy roses in February?’ - to champion positive change in the floriculture industry.

They hope to initiate conversation on the impact of buying produce out of season - in this case, roses for Valentine’s Day - and the effect that this has on supply chains that continue all year round.

Around 8 million roses (570 tonnes) are imported into the UK for Valentine’s Day to meet demand. But what do we know of these blooms we’re buying?

Where do these roses come from? How have they been grown and what of who grows them? What is the real cost of their production and our consumption of them?

Unfortunately, the way roses are grown for Valentine’s Day is more often than not, far from beautiful.

Instead of endorsing and reinforcing unseasonal consumer demands that maintain standards of practice that are unsustainable and unjust, how might we, as consumers in the global north, advocate for positive and progressive change within the global floriculture system?

SSAW hope that by opening up discussion over current common practices in the floriculture industry; adjusting consumer expectations and demand; and returning to a seasonally lead supply - positive, progressive change can be made.

We’re here to amplify SSAW’s campaign and support the conversation.

Why buy roses in February?

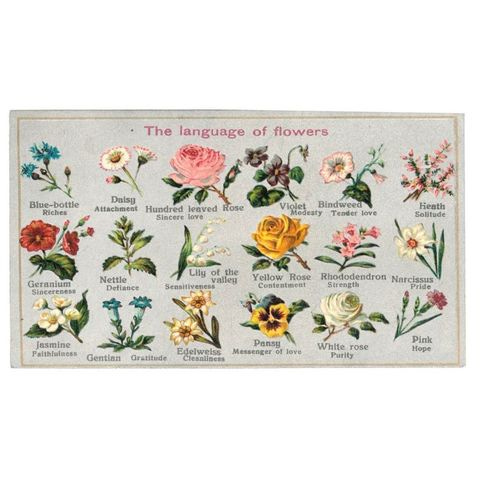

The associations between roses and romance is widespread across the world in many different cultures both east and west. The connection to love is deeply rooted.

From nightingales to Shakespeare, you can read about some of the legends and myths here:

Why not buy roses in February?

The issue is complicated with no straightforward answer, but as SSAW says, their findings do somewhat kill the romance of roses at this time of year.

Here are some of the key points:

Roses aren’t in season in February in the UK or in much of the world. They have to be grown in artificially regulated conditions even in countries with equatorial climates.

Environmental inputs are high (water, energy and pesticide usage etc.) and so too are the ethical impacts. This intense period of high demand for just a single date, means roses have to be held back or brought on by force. Overtime is often compulsory, on top of often already long hours with poor pay and working conditions.

In the UK, 80% of cut flowers come via the Netherlands, 33.3% of the roses imported into the EU are grown in Kenya. A dutch bouquet that includes 5 roses has a carbon footprint 32.252Kg/CO2, a Kenyan bouquet that includes 5 roses, equals 31.132kg/CO2. An equivalent bouquet using British grown alternatives just 3.287Kg/CO2. A locally grown bouquet using 15 stems of outdoor grown flowers just 1.71kg/CO2.

As flowers are not consumables, regulations on pesticide use are much less stringent. The UK produces pesticides for an international market that are banned for use domestically.

There is a problem of value distortion as a direct result of supermarkets - the UK's largest outlet for cut flowers as opposed to specialist flower shops in the EU - often selling roses as loss-leaders which doesn’t remotely reflect their true cost (economical, ethical or environmental). Despite increasing growing and transporting costs, roses are now more affordable than ever. At the other end of the scale, independent florists are having to spend more on rose wholesale costs - without being able to up their retail prices in a bid not to lose customers in such a highly competitive environment. This leaves both florist and grower at either end of the supply chain at a disadvantage.

SSAW are advocating for positive change within the global floriculture system. Boycotting imported blooms is not the answer as this would have a devastating economic impact, but it also doesn’t mean we have to accept the current status quo.

Find a fuller, in-depth and nuanced blog post about these issues from SSAW here.

What can we do?

How do we ensure that our decisions around food and floral consumption are as considerate of the planet as they are of the livelihoods of the people that grow the produce? SSAW readily admit it’s a continuous balancing act, the learning is continuous and there is no quick fix. On both the supplier and consumer side, it’s about the collective effort and conversation if we want to make an impact. Here are a few ways we can make a start:

Ask questions: have conversations with suppliers and consider the conditions in which our purchases have been produced, floral or otherwise. We can communicate our preference for ethically produced, sustainable flowers.

Consider the provenance and seasonality of the produce we buy, whether that’s food or flowers.

Be conscious in choosing to shop small: support an independent business or individual, and do it as locally as possible. There may be a small-scale grower within easy distance selling seasonal produce if you live in the UK.

Alternative gestures: Find SSAW’s list of alternative gift ideas for Valentine’s Day here:

As part of their campaign, SSAW are running a whole series of IG posts, including guest posts from floristry experts, about the complexities and nuances of buying roses for Valentine’s Day. You can follow the posts here.

You can also dive deeper into SSAW’s content over on their journal here.

Information in this article has been adapted from content provided by the SSAW Collective

Photo credit: Sui Searle